Zero is the Future of Money

By dropping commodity theories of money, and embracing credit theories of money, we can build something a lot more exciting than standard crypto

If you’ve had your political-economic awakening in the era of crypto-tokens, there’s a chance you may believe that faux-commodity tokens like Bitcoin are the first and only challenge to the monetary system. That, however, is like thinking Keto is the first and only alternative diet. Bitcoin promoters have spent years presenting it as being the antithesis to our normal monetary system, but in this piece I’m going to show you how to broaden your horizons beyond both of these paradigms. To do this we must blend thesis (1) and antithesis (-1) into a synthesis (0). I’ll start with a summary of our standard system and some of the problems within it, after which I’ll explore its supposed nemesis, and conclude by zeroing in on a synthesis.

1) Thesis

The dynamic (quasi)centralization of mainstream money

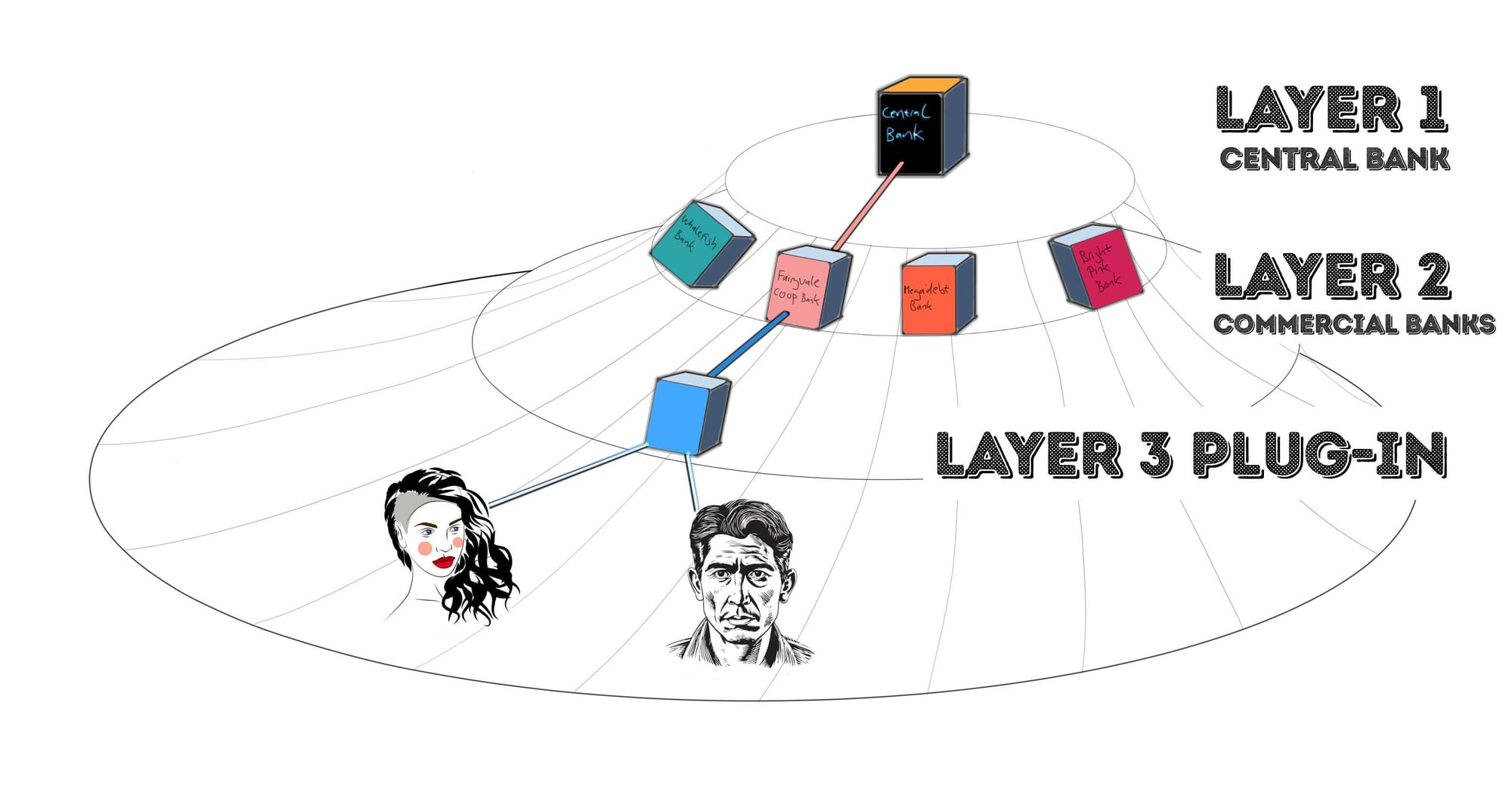

The world’s monetary system is underpinned by nation state institutions (central banks and treasuries), whose money forms the substrate upon which commercial banks issue out a second - and much larger - layer of ‘digital casino chips’ that we also call money, and that in turn form the substrate upon which various other players like PayPal issue out a third layer of money (to understand this in more depth, check out the Casino-Chip Society). There’s actually a fourth layer, but let’s keep it simple for now.

One way to visualise this is to think of state institutions - and the money they issue - as forming a centre of gravity for the other two layers (which you might imagine as being in orbit around this centre), anchoring them but not controlling them. This means state institutions only influence, rather than determine, the overall money supply. There are a large number of players that collectively preside over the expansion and contraction of the dynamic monetary web that we’re all enmeshed within.

There are two big features of this system we can focus on. Firstly, it’s hierarchical, with powerful state institutions anchoring powerful banking institutions that allow a whole range of third-tier players to plug into them, some of which are dodgier than others. We could say that it’s ‘centralized’, in the sense that an oligopoly of players oversee it and - to some extent - control it.

Secondly, it’s dynamic, rather than static, and its dynamism is also pretty unpredictable, rather than predictable. It pulsates, expanding and contracting constantly, and often at the same time, with expansions in some areas being neutralized by contractions in others. Every day money is being created and destroyed, and this is happening in all three layers.

To understand this without freaking out, you have to have a basic grasp of credit money, and the easiest way to understand credit money is to first focus on the much simpler example of a promise. We all have experience giving promises, so you should know that a promise only becomes a promise when you issue it to someone. This could be the point that it leaves your lips, or when you write it down and hand it to the person. In this sense, it’s ‘created from nothing’ through the act of issuing it. So, imagine I write out “I promise you a massage” and hand it to someone. If they hand it back to me the following day, and say “I’m ready for my massage”, they’re redeeming the promise, after which it’s taken out of circulation. In other words, if someone hands you back a promise you’ve issued, it gets retired or destroyed.

Money issuers in Layer 1, 2 and 3 are not handing out massage vouchers, but they are issuing out different forms of IOUs (legal promises). I’m not going to focus on the nature of these IOUs in this piece, but - like any type of promise - they are created when they are issued, and destroyed when they are handed back. This is why our money supply is dynamic. The nature of the dynamism at each layer, however, differs:

- Layer 1 money: Central banks and treasuries create new money when the government is spending, and destroy it when people, for example, pay taxes

- Layer 2 money: Commercial banks issue out new ‘digital casino chips’ when people deposit cash (Layer 1 money), but also when they’re giving out loans, and destroy those chips when people ask for cash back, or when loans get repaid (to learn more, see An Emotional Guide to ‘Fractional Reserve Banking’)

- Layer 3 money: Players like PayPal create new units when someone transfers Layer 2 money to them, and destroy those units when the person asks for that back into their bank account

We can also identify three separate styles of action that can happen in each layer

- Issuance: the money issuer issues money (often in exchange for something)

- Transfer: the money users pass the issued money between themselves (often in exchange for something)

- Redemption: a money user passes the money back to the issuer (often in exchange for something, or to get free of some obligation), thereby destroying the money

Many of us will have experienced different versions of all of these. Getting a bank loan is an example of being on the receiving end of Layer 2 Issuance, while getting a government grant is an example of being a beneficiary of Layer 1 Issuance. Handing cash to a shopkeeper is Layer 1 Transfer, while making a contactless payment for a train ticket is Layer 2 Transfer. Paying taxes is Layer 1 Redemption, while repaying a loan, or getting cash out of the ATM are examples of Layer 2 Redemption (this isn’t always immediately apparent, but going to an ATM is the act of redeeming your bank-issued digital casino chips for cash, and - similarly - repaying a bank loan is the act of returning chips to the bank).

These different layers of money, and the different styles of actions within them, are deeply embedded into our everyday lives. In fact, we might think of ourselves as being Layer 0. We are beings on a planet surrounded by ecological systems that we use for our survival, and we’re all interdependent, but we manage our interdependence through the monetary system, the dynamism of which has a complex multi-directional relationship to the level of production and consumption in our Layer 0 existence. Sometimes it’s easy to find work (production) and to get people to take what you’ve produced (consumption), and at other times it’s not, and much of what’s called ‘monetary policy’ is about trying to manipulate all that via the money system.

It helps to be able to visualise it in 3D, so here’s an imaginative exercise. Imagine the money system as being a kind of nervous system embedded in the underlying economy, and then imagine grabbing it and pulling it upwards to reveal the hierarchy of players: at the apex are state central banks, with commercial banks below that, and third-tier players plugged into them, and all of them locked into the broader financial sector, which is locked into the corporate sector, and then all of us below. Here’s a very rough stylised sketch I did to convey the basic idea…

From here we can point to four conceptually separate, but related, forms of dynamism in the system:

- The increases (issuance) and decreases (redemption) in the (3-layered) money supply

- The increases or decreases in the velocity with which transfers between money users take place

- The surges (booms) or contractions (busts) in the underlying production in the economy

- The increases and decreases in the power of the monetary units to command people to produce things or give you stuff (commonly called ‘deflation’ and ‘inflation’)

Trying to predict the behaviour of this collective entity, and the interrelated forms of dynamism that accompany it, is a dark (pseudo) science, but we’re all part of it, and we feel it even if we struggle to see the whole structure and its processes. There are many problems with the money system, but here are a few basic things we can say about it:

- There are better and worse versions of it: people often generically talk about ‘fiat money’, but our monetary system is actually a hybrid hydra and there are better and worse versions of it. For example, the version without physical cash (‘cashless society’) is definitely worse than the version of it with cash. I spend a lot of my time defending cash, because it’s crucial for maintaining a balance of power between Layer 1 and 2 money, and for preventing a more dystopian version of the system from emerging

- Bank power is as important as state power: banks can issue out huge numbers of digital casino chips to parts of the economy they wish to mobilise, and to pull those away from parts of the economy they want to shut down. This means they have a lot of power to decide what (and who) lives and dies in the economy, and they’re far more likely to choose wealthy property developers than a poor project in a poor neighbourhood. The banking sector (and the mega institutional investment industry that owns their shares) is often in complex alliances with states and the broader financial and corporate sector, and also presides (alongside lawyers and accounting firms) over a massive system of offshore finance obfuscation used by corporations, mafia and oligarchs

- Inflation politics: Looking at all the layers at once, we see there’s an ongoing dance with inflation, by which we mean the power of the monetary units to command real things from real people in the underlying economy, and that’s always in a dance with employment (the people in Layer 0 trying to find a way to survive by slotting themselves into a niche within the interdependent structure). In very crude terms, conservative monetary policy ‘hawks’ generally like to keep a bunch of people unemployed to try keep inflation low, whereas others often want to counter that

- Geopolitics: We live in a transnational economy, but the transnational money system is a patchwork of national sub-systems stitched together, and often that stitching takes place via the US dollar system, which gets a lot of power from this ‘reserve currency’ status (and a meta battle with China is emerging in this regard). The geopolitics increasingly also involves digital payments data: as former Ecuadorian central banker Andrés Arauz points out, giants like Visa and MasterCard are based in the Global North, and their increasing control of the payments systems of people in the Global South gives US agencies a whole lot of power to pry into their lives

I could go on listing more problems (such as the fact that the money system is largely built to interface with and accelerate the soul-eating expansion of financialised corporate capitalism), but needless to say there are a whole lot of different people who have different gripes about the system and the power held by the oligopoly of players within it. But what kind of alternative do you propose when faced with this amorphous beast?

-1) Antithesis

The rigid decentralization of crypto-commodity fetishists

Let’s talk about Bitcoin.

Hmm… actually, no. Let’s not rush into it. Before I start talking about crypto-tokens, I want to take a step back, and to talk about a mindset that precedes them, which is useful to understand.

If I was to issue you with a written promise for a massage, you’d have a strong understanding of its double-sided nature. It might be a single object, but it references two sides: Side 1 is me and Side 2 is you. I issued the promise to you. If any one of those sides is removed, it ceases to exist as a promise.

To put it in more technical language, a promise has both an asset and a liability side. The asset you hold - the promise - is from my perspective a liability: it’s something I owe you (if you turn that phrase into an acronym, you get IOU). If you were able to transfer this promise to someone else - for example, your brother - they’d take ownership of that asset, while my liability remains constant. I now owe your brother a massage.

Imagine a far-out scenario in which this promise gets passed around so much that the holders forget who issued it, and - moreover - come to see it not as a promise for a thing, but as the very thing that it promises. So, rather than seeing it as a massage voucher, they begin to see it as a kind of congealed abstract embodiment of a massage.

Something like this often happens in large-scale credit money systems. All the money units we pass between ourselves are liabilities issued out by states and banks (and various other third-tier players), but we often fixate on the asset side, and are very prone to generating crude mythologies of money as an object disassociated from an issuer. In this ‘asset only’ imagination of money, we picture it as a kind of abstract congealed incarnation of generic ‘value’, viewing it metaphorically like a commodity or a substance. This is the commodity orientation to money: it’s a way of thinking about money as if it were a commodity with use in itself.

There are various reasons for why this happens. One is that our money system is so huge and immersive that it’s very easy to go through life without seeing what’s happening in the background and to have no knowledge of the issuers. You simply learn as a child that the units have a mysterious power to command people. Another reason is that, unlike a massage voucher, the nature of the different promises in the different layers of our monetary system are obscure and hard to understand (and, moreover, are often framed in confusing circular terms). To go deeper into some of this mindset, check out my piece Money through the Eyes of Mowgli, where I argue that the existential experience of being in a large-scale capitalist system naturally leads your mind to generate crude commodity mythology around money by default, providing a folkloric way to describe its power over random strangers on the street. This is also hard-baked into the mainstream Economics discipline, which is built upon a commodity mythology of money (the core of which is the myth of barter: see How to Write a Flintstones History of Money).

Needless to say, many people end up with a commodity orientation to money, which, as mentioned, is actually a metaphorical way of thinking about money as if it were - or should be - a commodity. This, however, leads to a new problem: if you have that subconscious baseline viewpoint, but nevertheless come to have an awareness that modern money isn’t actually a commodity, it creates a cognitive dissonance that must force you down one of two paths:

- Path 1: Modify your concept of what a commodity is to calm the cognitive dissonance: Many people are aware that money isn’t literally a commodity, but nevertheless must find ways to describe it as if it were, and so default to thinking about it as a kind of mysterious ‘fictitious commodity’. The most common way to do this is to claim that we all just collectively decided - through an act of imagination or belief - to imbue it with value. It’s a bit like Peter Pan’s view of flying: money will fly as long as we all keep believing

- Path 2: See it as an imposter or fake commodity: I’ve given talks on global finance for over a decade, and I’ve lost count of the times when someone in the audience rants about how the real problem with finance is that money is ‘backed by nothing’, and that there’s no gold in the central bank’s vault, and that the system is therefore a giant Ponzi scheme made up of farcical units that are pretending to be a commodity, with some deceitful power that tries to force you to use them, or to deceive you into believing they are valuable

The latter position is a more angst-ridden response to the cognitive dissonance, with the person going around trying to sow moral panic about money somehow being ‘not real’. This position also tends to come along with (or perhaps generates) a reactionary idea of what money should be. For the universe to not be a topsy-turvy deceitful place, the fake money must be replaced by a money that is ‘created from something’ so that it has ‘real value’, and must not controlled by a corrupt authority.

Normally, this generates in the modern mind an imagination of gold. Most people have little understanding of how gold actually operated in the past, but simply assume that it somehow was a natural money system, perhaps imagining medieval fairs with people plonking little gold coins in exchange for chickens. I mean, pretty much all medieval-themed video games and modern fantasy shows like The Witcher have people searching for gold ‘coin’.

‘Goldbugs’ are people that channel the most politicised version of this belief, casting gold as the perfect ‘natural’ money, and contrasting it to the unnatural abomination of fiat money ‘created from nothing’. Gold certainly is created from something. Well, it was created by star explosions, and distributed in rock strata, and gold fetishists believe that uncovering this geology offers a better monetary policy than humans institutions do (provided we ignore the centuries of imperial slavery to obtain it, the 16th century conquistadores sent off to massacre indigenous South Americans to get it, and my home country of South Africa, where a fascist police state coerced poor workers to mine it well into the 1980s, so that goldbugs across the world could obtain the famed Krugerrand).

Despite its bloody history, gold is rigged up in the conservative imagination like a disapproving puritanical god that you can invoke as a protection against the depraved fiat system. Most interesting, however, is that its most important modern function is symbolic rather than practical. Very few people - including monetary conservatives - actually want gold to be money, but it serves an important function as an abstract Platonic Ideal to be emulated rather than used. The idea is to keep using the normal fiat system, but to constrain the minds of those who use it, such that they imagine it to be like a commodity with hard limits. Monetary conservatives have fought long and hard on numerous fronts to tie the fiat system up in commodity-centric mythology, law and language, and have succeeded, because many people do use commodity metaphors for money and often do believe that it’s inherently constrained (incidentally, this is something the MMT movement has slowly tried to deprogram, causing consternation among people on both the political right and left, who’ve got used to fighting each other within the bounds of the commodity framing).

So, with this background context in mind, let’s now move on to Bitcoin.

I’m going to assume you have a basic knowledge of what Bitcoin is (or at least, what it claims to be), and to focus in on its political message. Bitcoin gave new energy and direction to people who previously could only hark back to an imagined golden era of ‘real’ commodity money. Rather than bleating on about medieval Witcher fairs, it allowed the vision to be repackaged in a modern digital form, and also added some more radical elements that could disorientate and excite a lot of people across the political spectrum. Given that most people are unschooled in the political dynamics of money, and given that most have a commodity orientation pre-programmed into them, Bitcoin was well-positioned to seem like a miraculous, cutting-edge and practical cure to the evils of our current system.

To promote it, Bitcoin evangelists reduce the multi-layered and multi-playered modern monetary system into the single term ‘fiat’, and set it in binary opposition to Bitcoin, which is presented as the antithesis to its two key features: remember that the fiat system is, firstly, underpinned by a (quasi) centralized oligopoly, which, secondly, presides over an unpredictable money supply that’s ‘created from nothing’ and which expands and contracts. To be the binary opposite, you must have a system that’s not controlled by a centralized oligopoly, with units that are ‘created from something’, and which has a predictable supply that lasts forever, rather than expanding and contracting.

The most radical part of the Bitcoin equation is the attack on centralization, but ‘decentralization’ in crypto-speak has a very particular meaning. In the pre-crypto era, ‘decentralization’ used to mean breaking up a large centrally-controlled system into many smaller locally-controlled systems (like a bunch of city states declaring independence from a nation state, or a small town trying to partially detach itself from the national economy by encouraging localist economic projects). In the Bitcoin world, by contrast, ‘decentralization’ basically means replacing one large system governed by people with another large system not governed by people. ‘Decentralized’ means ‘a large automated infrastructure controlled by nobody’, although if you want to put a more romantic human spin on it you can say its ‘run by everyone, but controlled by no-one’.

The second part of the Bitcoin equation is a lot more overtly conservative. It’s an attack on the entire concept of an expandable-contractable supply of units. The system has a fixed supply of tokens that must (sort-of) be ‘produced’. I say ‘sort of’, because really they are written-into-existence, but the person - or, rather, computer rig - doing that must first exert a very large amount of energy. It’s a bit like having to pierce through a forcefield around a database before you can write something onto it, or having to climb Mount Everest before you can write out the number ‘50’ on its summit. This energy expenditure creates the illusion of ‘extracting’ Bitcoin tokens out of some kind of cyber-ore with a pre-programmed hard limit of how much ‘coin’ can be mined (the initial design is somewhat like the digital equivalent of the star explosions that arbitrarily decided how much gold crashed into the earth). In less metaphorical terms, the shared protocol that brings Bitcoin to life simply won’t allow participants in the system to write new units into existence after the arbitrary number of 21 million units is hit.

While credit money systems have that inherent dynamism that comes from the constant fluctuations of Issuance, Transfer, and Redemption, the Bitcoin system isn’t very dynamic at all. There really isn’t a true Issuance process: rather, the system has a machinic formula for spitting out ‘asset only’ tokens that have no liability side, which means there’s also no Redemption process. The most dynamic part of the system lies in Transfer: the units can be transferred around, but there’s no leeway to push more out or pull more in if there are changes in the level of ‘Layer 0’ production going on in the economy. In other words, there’s no such thing as discretionary Bitcoin ‘monetary policy’. That, of course, is part of the whole point, but it means the system is incredibly rigid, and - despite the rhetoric of fairness - also has some pretty horrendous problems with inequality. There’s a lot of dark fuckery that goes on in the fiat system, but it certainly expands with our population, whereas a disproportionate amount of the Bitcoin supply arbitrarily lies in the hands of a few thousand random early adopters. Consider the fact that there are almost 8 billion people on the earth right now - not including future generations - and yet the 21 million possible Bitcoin units were being given out in 50 token chunks to people who happened to be around in 2009 with the expertise, capital, equipment and peer groups to exploit it.

To justify the massively unequal initial distribution, many Bitcoin proponents rely upon dubious ideological positions (like claiming that the early users are being rewarded for being bold risk-takers) and semantic trickery, noting that there’s no problem in running short on units because a bitcoin can be split into smaller increments like Satoshis. It’s somewhat like noting that a tonne of gold can be split into 1,000,000 grams, without asking who owns the tonne of gold. So, one day the big holders of Bitcoin (people like Michael Saylor and Elon Musk) will be old, and future generations will have to wrest small fragments of Satoshis out of their wrinkled hands, a process that would presumably give those ‘whales’ an ability to extract huge amounts of labour from them in return. Given that most of these big holders basically did very little labour to get the original distribution, this is extremely problematic.

Even the decentralization claim starts to look a lot more dodgy when you notice that the style of decentralization promoted in traditional crypto-token systems is also designed to make the systems (theoretically) unchangeable. There was - at least initially - a rejection of human governance processes, which were seen as being corrupt, but that required the crypto-token movement to have an alternative account of how change could ever take place. This in turn was supplied by a libertarian concept of a market in pre-programmed systems (if I was being tongue-in-cheek, I might call it a ‘market in pre-programmed star explosions’). In much free-market ideology, the political act of voicing your concerns (‘voice’) is held in lower esteem that simply exiting a system you don’t like (‘exit’) and buying into another system, or starting your own system (this latter viewpoint is especially strong among people immersed in startup culture). For example, if you complain about Google screwing the world, some will tell you to stop whining and just go start your own search engine, as if each person had ten years, billions in capital, cutting-edge expertise, and massive market power to dislodge something that’s become unavoidable entrenched infrastructure in our society. This mindset was transferred to Bitcoin: rather than offering a governance process for changing it, you were told that if you don’t like it you could just fork off and start a different one. It superficially sounds appealing - and certainly lots of people made windfall profits by cloning the system and pushing out new tokens to be sold - but it’s politically vacuous, ineffective and unsatisfactory.

I could go into all the other problems of the Bitcoin system, like the incredibly energy-inefficient mode by which it’s produced, but by far the biggest issue is that it simply fails as money. Fiat money can run circles around Bitcoin because of its flexibility and dynamism, which means - like gold - Bitcoin tokens have simply become another commodity priced in fiat money on a fiat money market. This is why many people have become rich in dollars by speculating on crypto-tokens.

Furthermore, all the supposedly money-like elements of Bitcoin (for example, the fact that it can be exchanged for goods) can be easily explained with the concept of countertrade, which is something I bang on a lot about. Basically, the tokens have a primary and a secondary life. In their primary life, they are collectible objects that get a monetary price on the dollar market through speculation. That monetary price in turn gives them a secondary life as a countertrade object. Countertrade is the act of using something’s monetary price as a guide to deciding how much of it to exchange for something else that has a monetary price. You can in fact do countertrade with any object in a monetary market - including bread loaves, headphones, and sheets of plastic wrap - but normally it’s a clunky process. What’s unique about limited edition crypto-tokens like Bitcoin is that they are highly countertradeable because they are digital and easily transferable. Sending bitcoins to someone superficially feels like a ‘payment’, especially because the tokens have monetary imagery pasted all over them, but when you hand bitcoin over for a surf lesson at Bitcoin Beach in El Salvador, you’re actually paying with the token’s US dollar resale price.

This is a horrifying thought to many Bitcoiners, who prefer to remain in a state of denial about that, but - once you get Zen about it - it becomes obvious that Bitcoin doesn’t compete with the mainstream system, but rather rides on top of it. Unfortunately, in order to market this countertradeable collectible, all the promoters have to big it up as a kind of US dollar competitor, and in the process trojan horse a lot of conservative monetary ideology into the minds of idealistic teenagers (which I view as a pretty bad case of collateral damage).

I don’t critique Bitcoin with malice. In fact, there’s an innocence in many parts of the crypto scene, with a longing for predictability in an unpredictable world. But it’s this very dogmatic insistence on a rigid system in a dynamic world that’s the problem. The standard monetary system doesn’t run away from Bitcoin. Rather it rushes towards it to engulf it, seeing it as just another thing to be traded. Bitcoin’s attempt to emulate a commodity is precisely why it’s so easy to co-opt. You don’t fight a giant saltwater shark by sending a small freshwater crocodile into the ocean after it.

Perhaps that’s an unfair metaphor. From one angle, Bitcoin’s co-optability is part of its strength. In getting swallowed by standard capitalism, Bitcoin has managed to fuse itself into the system, and as it gets metabolised it comes to offer some interesting new routes to exchange via digital countertrade. That’s a type of success, but it’s far from the vision of replacing the monetary system.

Because the general public defaults towards having a commodity orientation to money, they are susceptible to believing straw man accounts of the actual monetary system, and this gives space to opportunists to offer straw man alternatives. Many big influencers in the Bitcoin - and broader crypto - scene have taken on this role, and have (arguably) channeled talent and public attention away from truly positive currency innovation, and into a largely counterproductive mosh-pit of speculation. These influencers now have large amounts of money and reputation that depend on them perpetuating the various forms of contradictory double-think that plague their systems, and a priesthood of crypto intellectuals have been enrolled to patch up the dissonance. They make almost theological arguments to try show why dollar-priced tokens are a competitor to the dollar, or why once it reaches a certain monetary price Bitcoin will somehow transform into being the monetary system, or why really it’s the dollar that’s priced in Bitcoin, not vice versa (the monetary equivalent of arguing that it’s actually the tornado that flies around the kite).

Many of these issues are also not unique to Bitcoin. They plague the crypto-token sector more generally, so let’s get real: there’s a lot of lovely and bright people here wasting energy and time following dead-end visions of money. This is why it’s imperative to find positive new ways to channel it.

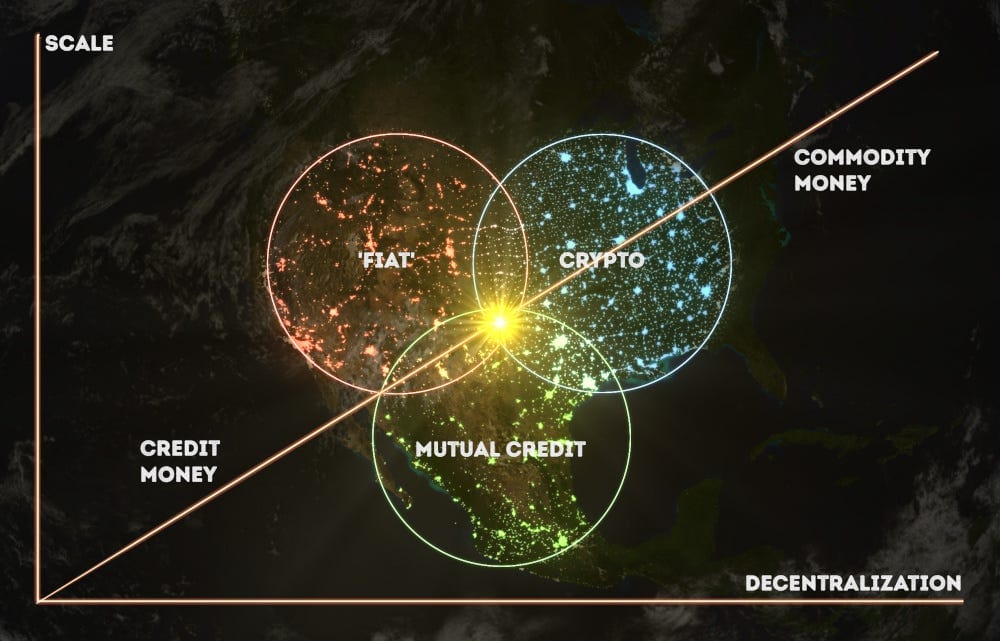

0) Synthesis

The dynamic decentralization of the credit commons

If the original crypto-token culture sought to attack two components of mainstream fiat, a synthesis might be achieved by attacking only one. What if we kept the dynamism of credit money, but combined it with a (modified) version of crypto decentralization? The mainstream system pulsates, expanding and contracting, but has a stacked hierarchy of players. You can imagine them on a vertical plane rising above us, but what if we were to pull that down to earth, flatten it, and aim for a pulsating system without the hierarchy?

To do this requires a new imaginative leap. One of the hardest things for most people to grasp is that we only experience the Asset Side of Money, and really only think of that side in terms of Transfer. We’re money users, rather than money issuers, and we mostly just transfer money units that were created by big institutions somewhere far away. We never experience ourselves creating money by pushing it out through Issuance, or destroying it by pulling it back in through Redemption. Most of us have never taken a peek behind the curtain to see the Liability Side of Money, and even fewer have experienced what’s it’s like to be active on that side.

In fact, some of the only people that have direct experience of that come from a small yet ancient tradition of alternative currency that pre-dates crypto by a very long time, and which also comes from a much older tradition of decentralization. Remember that ‘decentralization’ originally meant breaking a large distantly-controlled system into many smaller locally-controlled systems. This ethos is core to many anarchist, localist, and mutualist groups that have historically believed in peoples’ ability to locally self-organise in the peripheries, in the shadows of the towering central institutions of mainstream capitalism. It’s from this tradition that mutual credit systems, and their cousins - timebanks and LETS (local exchange trading schemes) - emerge.

Mutual credit is a simple, yet profound, alternative money system. Here’s how it works. You get a group of people together, set up a database between them, and allow them (or empower them) to pay each other by promise. ‘Paying by promise’ means one person can get something real from another person by promising to give them something real later. Essentially, they issue an IOU. When they do this, it’s recorded on the database, which keeps track of who has issued promises, and who has accumulated them. Everyone starts on zero, and if you issue a promise to someone to get something real, you go below zero, while the other goes above zero, their positive credits mirroring your negative credits. That’s an Issuance process, but the person with the positive credits can come back to claim stuff from you, which is a Redemption process that can take you both back to zero. To make it more sophisticated, you can allow Transfer, so that the IOUs can be moved around between the members, allowing people to accumulate IOUs that weren’t originally issued to them. Finally, you can set limits on how many promises people can issue, to prevent, for example, a person issuing a tonne of IOUs to get a tonne of stuff before running away.

If you’ve ever gone below zero on one of these systems, you’re one of the few people in this world to have experienced the process of being a money issuer. In a mutual credit system, money isn’t something that comes from a mysterious source far away, and it’s not something you must try grab and hoard like a squirrel grabbing an acorn. No, money emanates from you at the point at which you dare to issue a promise that will push you onto its liability side. You’ll also experience the process of destroying it, as someone with a positive balance comes back to demand something from you. Both sides are always in a dance with the zero line, fluctuating from the positive to the negative as they move in and out of obligation to each other by getting real things from each other.

There are two big things we can say about traditional mutual credit systems (and their relatives). Firstly, they tend to remain small. They are set up against the backdrop of the much more powerful fiat system, and they tend to only succeed when they find ways to interface with that system, or to not directly compete with it. This is why people often refer to these as ‘complementary currency’ systems. Many are run by volunteer groups who easily become burned out, or who see their work as a part-time community project rather than a full-time political mission. Some, like Sardex in Sardinia, have at times reached impressive scale, but many systems of self-issued and locally circulating credits (often denominated in all manner of idiosyncratic units) have stagnated or faded away. Some, like Eli Gothill’s Punkmoney system for issuing IOUs on Twitter, were designed to be short-term experiments. Needless to say, there’s been perennial attempts to link these systems into federations where they can get strength in numbers: see, for example, the Community Exchange System of former South African political prisoner and escapee Tim Jenkin (played by Daniel Radcliffe in the film Escape from Pretoria).

Secondly, from an intellectual perspective, the people who get involved in these systems tend to build a much stronger understanding of how the actual monetary system works. This is because small-scale mutual credit systems are built from similar principles - or primitives - to large-scale credit money systems. They also tend to imprint the highly unorthodox, yet incredibly useful, credit orientation to money into the minds of their users. A credit orientation to money is a mental model that sees money not as a commodity (either real or fictitious), but rather as an active accounting system powered by IOUs that bind people together into inescapable interdependent meshes.

As I discussed in Money Through the Eyes of Mowgli, the commodity orientation to money requires you to believe that people need to be induced into trade by dangling something of value in front of them. Credit thinking, by contrast, recognises that people are tied into non-optional interdependent networks, within which they’ll often have to ‘go negative’ to get access to the goods they need to survive before they can produce anything. Picture your lungs telling your heart that before it can oxygenate the blood required by the heart’s tissues, it needs energy delivered to its tissues via a pump of the heart. At a systemic level, there’s no fundamental separation between these interdependent parts in your body, and there’s no need for one part to ‘convince’ the other to help through some kind of incentive system. You can choose to imagine that your lungs and heart are ‘trading’ with each other, but it’s actually an inescapable form of cooperation. Once you start to see whole economies like this, it lowers the need to generate commodity mythologies about money.

Crucially, credit thinking leads to a vision of money as being a kind of nervous system, rather than a circulatory system, and the key primordial nervous impulse being sent along that system - to create its grooves - is the act of ‘paying by promise’. In our modern system, the issuance of these impulses is completely dominated by mega institutions, but there’s nothing to say that alternative versions of the same principle can’t be achieved, especially with the advent of new distributed technology architectures.

One subtle yet crucial nuance to internalise is that a credit orientation to money is a way of thinking about money, rather than a specific prescription or specification for its exact form. In general, what we call ‘credit money’ is an IOU that’s either printed onto physical objects or written down in ledgers, but credit money principles can actually be hidden in the background of many supposed cases of ‘commodity money’.

Indeed, while most people use a commodity orientation to think about credit money systems like fiat, you can also do the opposite and apply a credit orientation to think about a commodity system like gold. Once you do that, the history of money comes alive. This is because commodity thinking leads you to imagine a world of inert objects moved by independent people, whereas credit thinking requires you to imagine the world as an elaborate mesh of people keeping accounts of webs of promises, relations and obligations, sometimes using fetishised commodity forms like the Rai stones on the island of Yap.

This is where our synthesis really starts to take off. Older pre-crypto alternative currency movements carry with them a much deeper understanding of money, and also carry the seeds of powerful new currency designs, but they’re often too polite. They don’t design systems that encourage speculation, and as a result have had their voices drowned out by the noise of crypto maximalists who pump out pseudo-commodity tokens like machine gun bullets. The crypto clamour, though, has drawn in many very talented and idealistic people, and there’s a big opportunity to redirect their latent creative energy and technical prowess towards new hybrids. What if the best of crypto could be fused with the best of credit thinking? What if crypto could shed its rigid monetary theory, and what if mutual credit systems could shed their small-scale backwater feeling?

At the intersection of thesis and antithesis lies something very important, but by default this synthesis remains fuzzy because it needs to be worked out. Here’s a general direction of travel though. Imagine a ‘credit commons’ (a term coined by mutual credit pioneer Thomas Greco, and developed further by protocol designer Matthew Slater), a world in which horizontal networks of people-powered credit money link together to present a dynamic counterbalance to hierarchical credit money. In contrast to standard crypto, which is historically restricted to rigid transfers of rigid tokens with metallic imagery, these ‘paying by promise’ systems require us to move seamlessly between the positions of money issuer, money redeemer and money transferrer. They strive to be far more organic and embedded in actual communities, morphing in resonance with the underlying people who use them. New forms like rippling credit (or mesh credit) allow IOUs to ripple like dominoes through networks of people, perhaps even hopping great distances through six degrees of separation.

A growing community of innovators is starting to gather together under a vision of forming not only a credit commons, but to build what Informal Systems CEO Ethan Buchman likes to call ‘CoFi’ - collaborative finance. If you’d like a peek into some examples of the new groups that embody this ethos, check out ReSource, Trustlines, Sikoba, Circles, Mutual Credit Services and Grassroots Economics. I plan to go into depth on these and other projects in future episodes of my Unboxing Alternative Currency series for paid subscribers, but if you want to meet people working on this stuff, I also recommend a visit to the Commons Hub. Their events are a lot of fun.

Let’s close with two final considerations.

Unfreezing Decentralization

The original style of decentralization in crypto is purposefully designed to ‘freeze’ the systems in place. Rather than having human governance processes, they rely upon various technologies and methodologies (like game theory and crypto-economics) to dis-incentivise bad actors from coordinating. They aim for large-scale digital systems that default to a pre-programmed set of rules that theoretically protect the average user, but often do so at the expense of any kind of dynamism or political voice for that user. Sometimes they try to freeze into place elaborate automated methods to artificially replicate dynamism and voice, and that’s an authentically interesting technical challenge for engineers, but it gets a whole lot more interesting when that mentality gets combined with - or offset by - an in-depth appreciation and focus on real human communities at a local scale (who really don’t operate like algorithms). One of the biggest cultural tasks is to bring the wealth of community-focused knowledge possessed by mutual credit practitioners into the crypto sector, whilst finding a positive outlet for the technical prowess of the techies: if done right, we might end up with more dynamic forms of liquid decentralization, with local systems riding on global architectures, using combinations of different governance systems for different scales of decisions.

Learning to love zero, and below

Commodity thinking imagines money as positive units of some ‘substance of value’, but credit thinking recognises that the substance of value in an economy is other people, and that holding a claim on those people is only a reality if they have something to give. Your positive unit is an asset to you, but to other people it represents a claim upon them. Your 1 is their -1, and, on average, a healthy state of interdependence seeks to always fluctuate around 0.

This is a highly stylised account, but one of the most profound things that emerges from this is the realisation that if your system only consists of a bunch of ‘asset only’ tokens with positive numbers - e.g. 21 million units of Bitcoin - there isn’t actually 21 million units of money in the system. Rather, what you’ve attempted to do is to rename 0 - the state of interdependent equilibrium - with a positive number.

Here’s a simpler example: If you have a 1000 interdependent people and you give them all 1000 units to start with, it’s pretty much the same as giving them nothing. Money is only created when one of them enters into a state of obligation to another: when 0 is transformed into -1 and 1. If you’ve simply renamed the starting point as ‘1000’, then it’s only when one person goes to 999 and another goes to 1001 that 1 unit of money has been created.

That takes a while for most people to get their heads around, but the point is this: the original crypto systems suffer from the fact that they were built to push out tokens with positive numbers, without any liability side. That may superficially make them look like money (after all, most of us normally only see the positive number side of money), but if you take a systemic viewpoint and imagine a scenario where traditional crypto-tokens actually became a money system (rather than countertradable collectibles), our economy would have to organically rebase the asset-only tokens to give them a liability side. This is an example of using a credit orientation to think about a supposed commodity money.

The big challenge for building authentically interesting alternative money is this. Because most of us are so used to associating money with positive numbers, we remain on the ‘receiving end’ of money. It’s only when we learn to love zero, and below, that we take that step towards claiming the issuing end.

Want to comment? Visit the original version of this article and join the discussion.